Introduction

IN THESE difficult times due to the COVID-19 pandemic, big and small businesses are in search of the fastest way to respond to the situation. Particularly for the food industry, business recovery and survival require close attention to food safety, quality, and retention of consumer acceptance. To meet these requirements, a scientific approach to their measurement and ultimate sustainability need to be developed and properly utilised. Quality emphasises prevention which is a must for food safety. To support this need, a well planned sensory evaluation program should be designed and effectively implemented in the company.

Food safety, quality and sensory interface

“Quality” is defined by the International Organization for Standardization as “the ability of a complete set of realised inherent characteristics of a product, system or process to fulfill requirements” (AJA, 2000). The statement implies knowledge of product characteristics which for food is mostly sensory in nature and how the processed product assures consumer satisfaction.

“Food Safety” is defined as a situation when food is rendered free from all types of contaminants (chemical, physical and microbiological) such that when eaten no illness will occur (Gatchalian, 2007). To achieve this, the food service or processing company has the obligation to ensure that its operation is adequately controlled to prevent loss of safety while still retaining the sensory qualities required by the consumers. It is, thus, imperative that food sensory attributes must be carefully observed and monitored since these provide the first indication of possible loss of food safety and quality.

“Sensory Evaluation” is defined by the Institute of Food Technologists as “a scientific discipline used to evoke, measure, analyse and interpret sensations as they are perceived by the senses of sight, smell, taste, touch and hearing” (Gatchalian, 2019). To date, various scientific methods of sensory evaluation have been developed, still many institutions have yet to accept its importance particularly when it pertains to sustainability of food safety and quality.

Quality, safety and sensory measurements in food processing

In food processing operations, four major steps are carefully planned and executed as follows: (1) Inspection of incoming raw materials; (2) Meeting in-process requirements or specifications; (3) Assessment of finished product quality and safety; and (4) Monitoring product shelf-life and acceptability. At each of these steps, measurements are required to obtain evidences or data about the product that ensures absence of : (a) contamination like chemicals (insecticide or fertilizer residues; residual antibiotics, allergens, etc.) or physical (stones, wood, metal, etc.) or microbiological (yeast, molds, salmonella, coliforms, etc.) and (b) significant deviations from specifications affecting product quality, yield and consumer satisfaction. Measurements will involve sensory evaluation, physicochemical and microbiological tests at certain steps of the process:

Step 1: Inspection of incoming raw materials. Figure 1 shows an example of raw material (Saba banana) inspection for the production of banana chips. Among the many inspection requirements, the first is “visual inspection” using company specifications. At this step, a well-trained “sensory evaluator” like an “Expert” on specific characteristics or a “trained Panelist” facilitates the inspection process. The final decision to accept or reject the delivery is facilitated through early detection by visual (colour, size shape), finger-feel and odour assessments, supported by other instrumental tests. Thus, with proper sampling, raw materials not meeting sensory requirements can be subject to rejection or acceptance. Other information about the raw material are obtained from the supplier’s Certificate of Analysis (COA) and other supporting data required by the customer. At this step, sensory evaluation provides an early indicator of probable risks to product safety.

Fig.1. "Saba” bananas are “visually” inspected based on the raw material specifications

Step 2: Meeting in-process specifications. A product like “hotdog” for instance, undergoes several processing stages and one of them is “emulsification” of meat mixture which will affect finished product quality if this step is not adequately controlled. High salt level of the meat emulsion can cause “sweating” of the hotdog during cooling (after showering step). Thus, while still at the “emulsitator”, a “salt expert” would check the emulsion for salt level. The “expert” was 99% accurate (tested chemically) in salt level identification, although initially she was a janitress. She was observed to have high sensitivity to salt and got developed into an “expert” for salt in the company. At the “in-process” step when there is still the possibility to make adjustments, a ‘sensory test” can be done to prevent a defective batch production which can be very expensive.

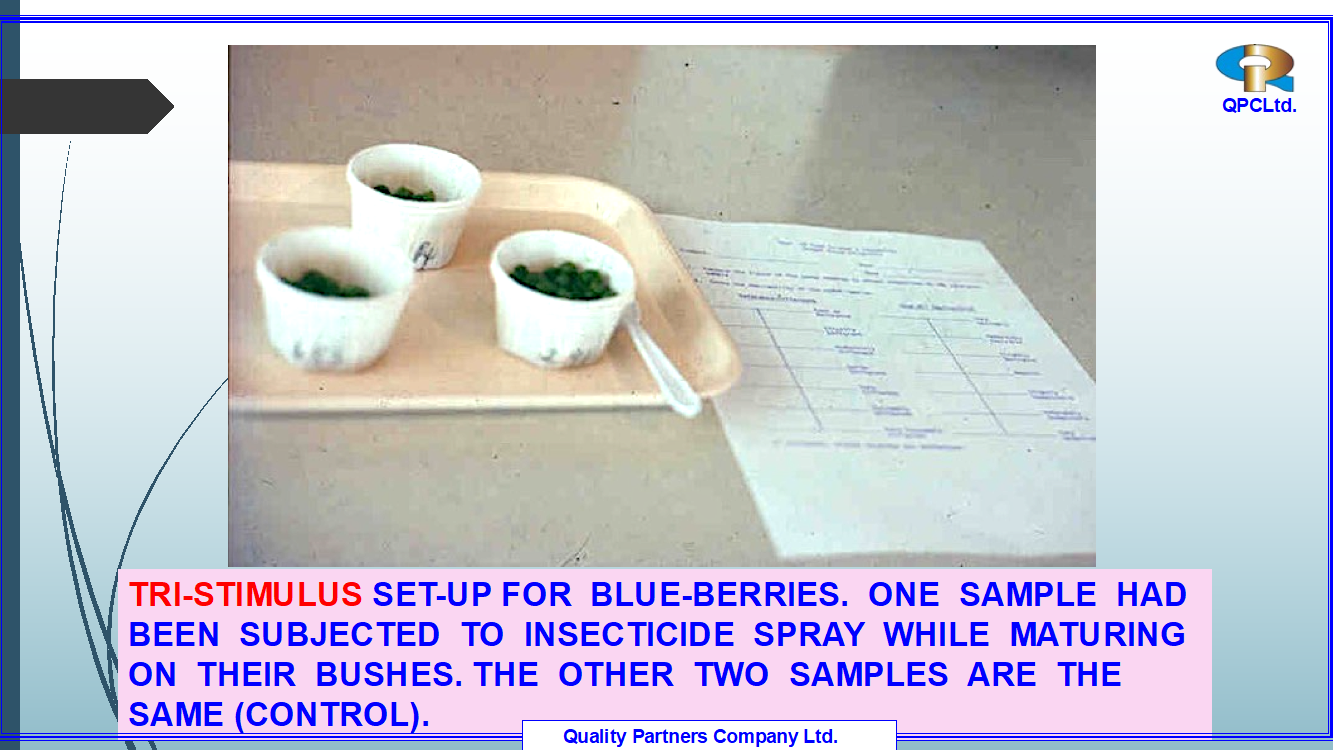

Step3: Assessment of finished product for quality and safety. Once the processing step is completed, the finished product is subjected to tests to determine effective controls while still in-process to ensure consistent finished product quality and safety. At this step, properly selected samples of the finished product are evaluated to check that all company specifications have been met to achieve desired quality, safety and consumer satisfaction. Figure 2 shows the “triangle test” for simple difference (Gatchalian and Brannan, 2011) to determine if a new batch production is significantly different from an already accepted one. A significant difference implies the need to review the product and/or process to determine risks of losing food safety and/or confirm deviations from a set quality standard.

Fig.2. Triangle test for simple difference between products

Since quality is focused on prevention, then tools that promote early detection of possible deviation from specifications or probable loss of food safety, are very important especially in food processing. Sensory evaluation methods have been found very useful in this regard and “evaluators” are the “instruments” that provide the information for decision-making. There are four types of “evaluators”: (1) Expert judge; (2) trained Panelists; (3) Consume-type Evaluators and (4) the Consumers themselves. Each of these performs measurement functions at different steps in the operation. For example in Step 1, the inspection function could be done by an “expert” on specific product attributes or by panelists trained for raw material inspection. For measures of difference whether in Step 2 or 3, trained laboratory panelists can be utilised (Ennis, et. al. 2014). To determine consumer satisfaction, either the “consumer-type” test shown in Figure 3, involving company employees representing target consumers (cheaper to implement) or the target “consumers” themselves can be employed.

Fig. 3. Consumer-type test to determine comparative preference

Step 4: Monitoring product shelf life and acceptability. It is of great advantage to the food processor to do shelf-life studies of all its products regardless of its nature and type of packaging. It is important to know how long a product can remain safe while still retaining sensory attributes required by consumers. For packaged products, “consume before” date on the label is expected to guarantee the length of time before a product loses quality and safety. During storage studies, several types of tests are done to determine changes through time. For food products, it is always best to relate the observed physicochemical or microbiological changes with variations in sensory characteristics. Figure 4 shows colour comparisons to determine the correlation between instrumental tests (chemical and physical) with sensory perception. Sensory test results from trained panelists are used to either predict product quality or as indicators of food safety loss caused either by microbial or physicochemical changes while on storage under simulated normal or accelerated conditions.

Fig 4. Colour change determination at different storage periods.

Employees’ sensory consciousness - role in food safety

Food safety sustainability is one of the major problems in many food companies because through time people tend to back-slide or be relaxed on maintenance of food safety at work (Villanueva, 2006). The existence of an active and continually updated “food safety program” can provide assurance of sustainability. Commitment to these practices through mind-setting involving everyone in the whole organisation as in a Total Quality Management (TQM) situation will almost always guarantee quality and food safety sustainability. Development of “sensory consciousness” in the total environment is a major support to maintain cleanliness and orderliness since these habits utilize visual and odor sensations as warning signs of violations of food safety requirements (Gatchalian, 2007). These early warning signs observed through a well-defined sensory evaluation approach, once embedded in the mindset of employees, contribute to early identification of risks to food safety leading to preventive actions.

Conclusions and recommendations

Prevention is the most important goal of quality (safety and acceptability) especially in the food business because once a poor-quality product reaches the consumers, it would be too late to overcome its effects particularly relative to consumer health. It is therefore an obligation of any food processing company to ensure that their products have consistent quality that guarantees both consumer safety and satisfaction. It is imperative that both quality and safety are sustained throughout the product life. One of the approaches favouring this situation is the scientific application of sensory evaluation methods embedded as a mindset of employees company-wide. To achieve this, it is urgent to have a well-planned, designed and executed sensory evaluation program that provides early indicators of food safety loss with assurance that consumer-required sensory attributes are maintained. Thus, quality and food safety become sustainable through time with effective application of sensory evaluation methods company-wide.

Literature cited

AJA Registrars. 2000. ISO 9001:2000 Standard, Auditor Transition Training Course. Madrigal Business Park, Acacia Ave. Ayala Alabang, Muntinlupa, Philippines.

Ennis, John M; Rousseau Benoît and Daniel M. Ennis 2014. Sensory Difference Tests as Measurement Instruments: A Review of Recent Advances. Journal of Sensory Studies. Vol. 29, Issue 2.

Gatchalian, M.M. 2019. Sensory Evaluation: A Must in Food Innovation. FoodPacific Manufacturing Journal. Vol. XIX NO.9 ISSN 1608-7100 Ringier Trade Media Ltd.

Gatchalian, M.M. 2007.Quality Employees: Their Role in Promoting and Sustaining Food Safety. Keynote Speech Proceedings.13th Asia Pacific Quality Conference and 7th Shanghai Association for Quality Congress October 18- 20, 2007, Shanghai, China.

Villanueva, Lorraine F. 2006. Food Safety in the Formal Food Sector: A Communication Study. Unpublished Dissertation - College of Communications, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines